Excavating early medieval Britain’s most significant female burial

Archaeological work just outside Northampton has uncovered an internationally significant burial, furnished with a remarkable 7th-century necklace, as well as a number of other high-status grave goods. With conservation and analysis of the finds under way, Carly Hilts spoke to Paul Thompson and Lyn Blackmore about what these artefacts can tell us about the woman they were buried with, and what they could add to our understanding of early medieval England as research progresses.

The site at Harpole, a village four miles west of Northampton, had been a very straightforward excavation for the small team from MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology. Working ahead of a new housing development by Vistry Group, and supported by archaeological consultants RPS, they had already carried out geophysical surveys of the whole area, and in March and April of 2022 they moved on to targeted excavation of the features identified by this preliminary work. For some weeks, they had been uncovering Iron Age and Roman remains: fairly typical domestic evidence, including ditches, pits, a couple of enclosures – not the main focus of a settlement, but traces of very everyday activity on the fringes of occupied areas. As the project drew to its end, there was nothing to indicate anything unusual – and then, on the penultimate day of digging, everything changed.

On 11 April, Site Supervisor Levente-Bence Balázs was overseeing the investigation of what was thought to be an interesting rubbish pit-type feature containing organic remains, but as the team carefully scraped back layers of soil, they found two gold items and pieces of human tooth enamel. It was quickly apparent that this was not a rubbish pit, but a grave. The archaeologists had uncovered the first hints of a discovery that would completely change perceptions of the site’s significance: the 1,300-year-old burial of a woman who had been laid to rest in ostentatious style, accompanied by the richest necklace of its type ever found in Britain. It was, Project Manager Paul Thompson said, ‘an exhilarating day’.

RECONSTRUCTING THE HARPOLE TREASURE

Now that all of the elements of the necklace have been recovered, it is possible to piece together the original appearance of the item, which has been dubbed the Harpole Treasure. Fortunately, the grave had been dug particularly deep, meaning that it had not been disturbed by ploughing over the years, and MOLA have been able to reconstruct the necklace’s likely design based on the position of each of its 30 components in the ground. These include nine oval pendants made from colourful glass and semi-precious stones set in gold, and eight late Roman coins. These were all issues of Theodosius I (r. 379-395), which MOLA finds specialist Lyn Blackmore notes are very rare in England, with only a handful noted in the most-recent survey (2010). The Harpole coins are in exceptionally good condition, suggesting that they had not circulated widely as currency. Instead, they may have been recovered from a hoard before being incorporated into the necklace, or carefully curated and passed down as heirlooms. It is also possible that they are later copies; analysis to determine this has not yet been done.

All of the coins bear the same design, with Theodosius’ profile on the obverse, and a motif depicting two seated emperors with a winged figure of Victory between them on the reverse. Because of how the clasps were fitted when the coins were turned into pendants, we can see which side was intended to be the ‘front’ on the necklace – and, interestingly, it is the reverse of the coins that was selected to face forwards. This might be because the imagery of the emperors, whose heads appear to be encircled by haloes, and the ‘angelic’ winged figure, were thought to be more appropriate for the religious theme of the necklace as a whole.

The wearer’s beliefs are expressed most clearly by the jewellery’s centrepiece: a roughly square gold pendant with red garnets forming a cross design. Like the coins, this was a repurposed piece: it appears to be half of a hinged clasp, not unlike a daintier version of the famous Sutton Hoo shoulder clasps. On either side of this was a large, biconical bead made from wound gold wire, while ten smaller ones were interspersed through the rest of the necklace. Altogether, when new and sparklingly clean, this would have been a visually arresting piece of jewellery, flashing with colour and gleaming precious metal: an unmistakeable sign of both the status and the piety of its wearer.

As for the necklace’s date, it is thought to have been made c.AD 630-670, when Harpole lay within the early medieval kingdom of Mercia. There are a small number of parallels from Britain, the closest being the Desborough Necklace: another Northamptonshire discovery, it was found just 20 miles from Harpole in 1876 and is now held by the British Museum. Although the Desborough design was much simpler – albeit with more (37) components than the Harpole Treasure – it too was hung with a number of pendants, and included biconical gold beads and a central cross.

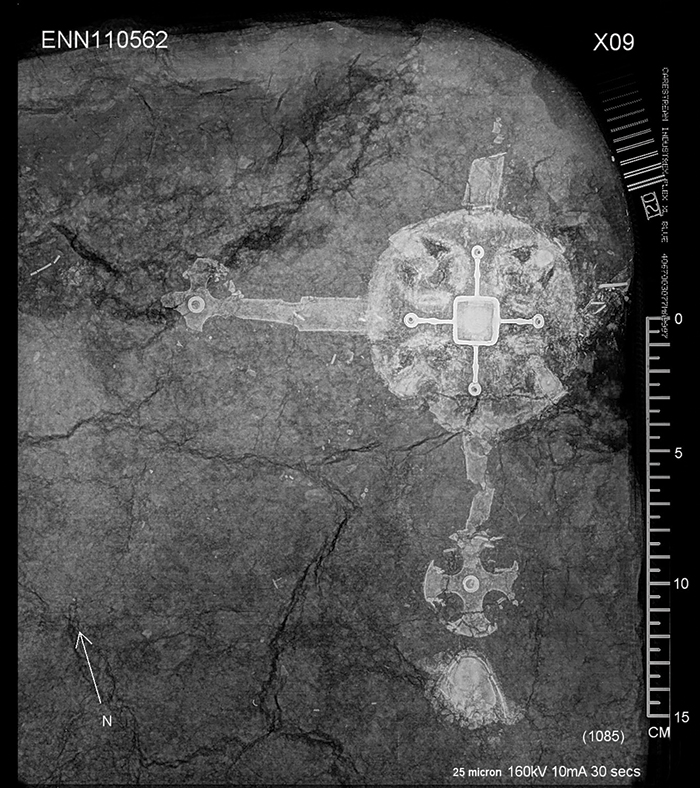

ABOVE LEFT: X-ray analysis of a soil block taken from the grave revealed the presence of a large and ornate cross within it.

ABOVE RIGHT: The cross was decorated with small silver faces with blue glass eyes. IMAGES: © MOLA

This is an extract of an article that appeared in CA 395. Read on in the magazine or on our new website, The Past (click here to subscribe), which details of all the content of the magazine. At The Past you will be able to read each article in full as well as the content of our other magazines, Current World Archaeology, Minerva, and Military History Matters.

considering most of the initial ‘Roman’ army and attached staff from AD43 to AD 410 were ‘Germanic’ it is likely that these people continued running the ‘Angarion’ and other services until their decline in the 5th and 6th centuries … This would explain current R1b106 DNA of English , the lack of ‘invasion’ evidence, and finds such as this – a family heirloom from ‘anglo-saxons’ in roman service.