The untold story of emigration and object mobility from Roman Britain

Britons are traditionally believed to have taken scant advantage of the opportunities to travel that the Roman Empire presented. But do tantalising clusters of brooches tell a different story? Tatiana Ivleva has gone in search of the Britons abroad.

Sometime around AD 80, two Dobunnian tribesmen in their early 20s, living near modern Cirencester, were recruited into one of the most powerful organisations of the ancient world: the Roman army. Before the year was out, they had left their native island alongside the auxiliary cohort they enlisted in. They never returned. Both young men stayed with their unit as it journeyed across the Channel and around the Continent – travelling from Britannia to present-day Hungary and Serbia – but their destinies were very different.

Of the pair, it was an infantryman, Lucco, son of Trenus, who was undoubtedly the most fortunate. He survived the harsh realities of three Pannonian Wars (AD 92-95), and then the inferno of the First Dacian War (AD 101-102). With the sort of luck that must have felt like divine intervention, Lucco missed combat in the Second Dacian War (AD 105-106) by mere months; he was discharged from the army in January AD 105, just before hostilities commenced. On his retirement, he settled in the lands of the Azali, near modern-day Szo˝ny in Hungary, alongside members of the tribe of his wife, Tutula, daughter of Breucus, and their three children: Similus, Lucca, and Pacata.

The second Dobunnian tribesman – Virssuccius, son of Esus – did not fare as well. This cavalryman and standard-bearer perished in AD 95 or 96, possibly from a wound received in the Third Pannonian War. Today, Virssuccius’s ashes, buried by his friend, Bodiccius, and his son, Albinus, rest in Stari Slankamen, Serbia.

British ‘old trousers’ and ‘baskets’ abroad

Our ability to reconstruct in some detail the biographies of these two Britons abroad is rather extraordinary. In most cases comparatively little is known about the young men recruited in the late 1st century to serve in units comprising British tribesmen, or those who joined the army of their own volition as volunteers and mercenaries. A rather modest epigraphic record suggests that few Britons emigrated in the Roman Empire. In all, 41 people of British descent can be identified. Yet only 28 men and women wished to declare their British ancestry; others can be deduced from analysis of their given names or what is known of their biographies.

Since the close trade connections between Britain and the Continent that flourished during the Roman period had existed since the Late Iron Age, one might expect that numerous Britishborn traders would have opened warehouses and done business across the provinces. Yet, surprisingly, only two probable British-born traders have entered the annals of history. One, Aurelius Atianus, was buried by his wife of 20 years, Valeria Irene, in Lyon, France. Unfortunately, neither his profession nor his reason for being in Lyon appear on his funeral monument, but the city was a commercial hub that attracted both wealthy merchants and craftspeople from far afield. Aurelius Atianus may have been one such trader, seeking out a market for British wares in Lyon.

Most British emigrants were men, but three women of British descent have also left traces in the epigraphic record. Two British women living abroad – Catonia Baudia and Lollia Bodicca – are named on the funerary inscriptions that they personally erected to commemorate their husbands. Both women were wives of legionary centurions, and followed their husbands quite literally until death parted them. Catonia’s husband, Flavius Britto, passed away in Rome, while Titus Flavius Virilis, a lifetime companion of Lollia, was laid to rest in the North African province of Numidia.

The third British woman, Claudia Rufina, was praised by the Roman poet Martial on numerous occasions for being an educated woman who had embraced the Classical way of life. She, too, was the wife of a legionary centurion, and doubtless enjoyed a privileged status while living in the heart of the Empire. Martial himself penned a couple of humorous remarks concerning Britons in two of his epigrams: ‘old trousers of a poor Briton’ and ‘barbarian basket that came from Britain’. The ‘barbarian basket’ is particularly enlightening, as over time, despite its provincial background, the basket became more Roman, presumably parodying the adoption of Classical culture. Sadly, Martial did not record any of British-born Claudia’s responses to this wit.

Another gap in our knowledge falls between the rather dry information noted on inscriptions: the age at death, land of origin, and professional affiliations of Britons abroad illuminates little about their personal experiences with, or feelings about, life overseas. One epitaph might seem to buck this trend, by expressing homesickness following the dedicant’s forceful removal from his native land. This funerary monument commemorated a centurion, Caius Cesennius Senecio, and was erected by his freedman Caius Cesernius Zonysius. Right after the name of the freedman a curious sentence appears: ‘Zoticus fetched (him) from Brittania’. Who this ‘him’ refers to is rather puzzling. Some scholars suggest that it was the cremated body of Senecio, repatriated by Zoticus in accordance with Zonysius’s wishes. Alternatively, was Zonysius himself sold as a slave in Britain, before being brought to Rome by Zoticus and purchased by Senecio? If the latter reading is correct, it points to the ex-slave not forgetting his roots, which he seems to have been only too eager to emphasise on his owner’s epitaph.

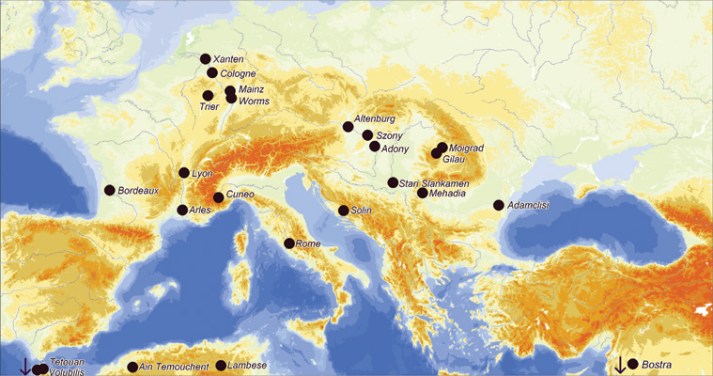

From the snippets of stories preserved on these inscriptions, we learn that Britons could be active, avid travellers. Their inscriptions are distributed across the Empire: from North Africa to Lower and Upper Germany, from Gaul to Roman forts on the Danube frontiers. New evidence also indicates that some Britons went as far as modern Syria. An epitaph published decades ago, and subsequently overlooked, records a Briton holding the high-ranking office of legionary centurion. This has only very recently been rediscovered during research on mobility in the Roman-period Near East by Laurens Tacoma and Rolf Tybout of Leiden University. While the presence of Britons in some territories clearly stemmed from military expediency and the whims of Roman officials, other individuals (Atianus, for example) seem to have settled abroad in search of the good life.

In brooches we trust

The epigraphic record is only one part of the story of Britons abroad. Small, portable, personal finds can shed new light on an issue that is obscured by the scarcity of epigraphic information. While common sense urges us to accept that many objects made in Roman Britain could travel abroad as trade exports, or even tourist knick-knacks and souvenirs (see CA 222 and 264), items of personal adornment and high-status jewellery may also have reached their overseas destinations via other routes. Ongoing research on the occurrence of such items, particularly British-made brooches, provides an opportunity to examine the various mechanisms by which objects could spread across the Continent. In total, around 250 British-made brooches have been recorded at 100 Continental sites, and the number continues to grow. Just like the epigraphic evidence, brooches were not confined to a particular Continental province, although most finds have occurred in the Empire’s frontier regions. By contrast, very few have been found in the Danube and Mediterranean regions.

Why brooches? What makes them particularly suitable for tracing the mobility of people travelling from Roman Britain to the Continent? These accessories were worn on the upper part of a garment, and served to hold two pieces of together. Functioning primarily as clothes-fasteners, they fulfilled a similar role to modern buttons, and could be highly ornate. Men and women wore brooches in most provinces of the Empire, where provincial apparel and accessories existed alongside mainstream Roman dress and jewellery. In Roman Britain, regional brooch styles developed, with idiosyncratic designs, decoration, and forms. For example, the use of both enamelled decoration and the headloop, which was purpose made for the attachment of a chain, are typical British brooch characteristics.

The distinctiveness of British-made brooches also resides in their various forms. There is the so-called ‘dolphin’ shape, named for its resemblance to a dolphin’s back; the trumpet shape, named after its similarity to the musical instrument; or the unambiguous and unique dragonesque form. While brooches displaying typically British characteristics appear to be relatively numerous in Britain, those found overseas account for at most 3% of the total number of brooch finds excavated on a site. Their scarcity abroad adds to the likelihood that these brooches were exclusively manufactured in Britain, rather than replicated by Continental artisans using templates. It is not unreasonable to attribute a variety of dynamics to the Continental occurrence of British-made brooches. First, brooches ‘travelled’ because they functioned as clothes-fasteners. After all, the people travelling from Britain to the Continent needed something to keep their clothes on. Second, consumers who purchased brooches in Roman Britain may have treated them as memorabilia, and not just objects for personal use. Third, as recently suggested by Bern Steidl and Fraser Hunter, the occurrence of brooches could also be related to the export of British woollen cloaks to the Continent, with these distinctive brooches acting as a badge of quality.

Naturally, a degree of guesswork is sometimes necessary to reconstruct the patterns of movement of peoples and artefacts, but combining these discoveries with both the distribution of epigraphic evidence and careful chronological analysis enables us to start reconstructing real mobility, as opposed to the movement of artefacts via trade networks. Quite a few British-made brooches were found at military sites on or in direct proximity to the frontiers where epigraphic evidence suggests that troops from Britain were stationed. This conspicuous cluster of artefacts on sites associated with either British auxiliary units or units transferred from Roman Britain reinforces arguments that the objects were carried by soldiers and family members who originated from or had lived in Britain for decades.

Fraser Hunter has brought to my attention a find that is particularly interesting in this regard, yet it is not a brooch at all. A tankard handle made in Iron Age ‘British-Celtic’ style was found in a Roman cemetery at Intercisa, a frontier military post situated in modern Dunaújváros, Hungary. Although the precise period that a British regiment was in residence is disputed, we know that Intercisa was occupied in the first decade of the 2nd century AD by the First Cavalry Regiment from Britain: the ala I Britannica. There is no way to determine the exact reason for the object’s presence on the Danubian frontier. One can speculate that it was either a family heirloom cherished for its association with Britain, or simply a handle attached to a favoured drinking cup used by its owner(s) for years and years. Regardless, the tankard handle was important enough to be brought all the way from Britain, as were two British-made brooches that were found nearby, also at sites associated with British military units.

These are not isolated examples. Brooches and other objects manufactured for personal adornment or use have emerged on Continental sites directly connected with British military units. For example, in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, more than 40 British-made brooches have been found, as well as a ‘British’-style mirror and flask. The presence of all these artefacts can be connected to a British detachment stationed at the legionary fort at the beginning of the 2nd century AD. There is also the Wetterau–Taunus frontier area in Germany, which was the main combat zone during the Chattian War of AD 82–83, and where 12 brooches were found. Inscriptions suggest that troops raised from Britain were deployed in this conflict, and later helped to construct and garrison a new frontier line along the mountainous Taunus ridge. At two such forts, Saalburg and Zugmantel, excavators have reported uncovering 21 British-made brooches.

He served in Britain and all I got was this brooch…

One thing to bear in mind, of course, is that wearing or having a British-made object would not have made someone ‘British’. Brooches say nothing about the ethnic origin of people who acquired them, since people of diverse origins could bring these personal decorations to the Continent. It is entirely possible that Continental-born soldiers serving in units posted to Britain could have returned to their homelands after 25 years of service, bearing souvenirs or jewellery executed in a style that they had become fond of. Indeed, a quarter of all British-made brooches found on the Continent were unearthed on sites within regions occupied by tribes that are known to have supplied recruits to units stationed in parts of Britain. On their return home, these veterans could have used the brooches in countless ways other than as dress accessories.

Brooches from cremation burials at sites associated with these veterans are often found in good condition and unburned, which indicates that they were deposited after the deceased was cremated. This suggests that the brooches played a functional role, such to fasten a bag or cloth containing the cremated remains. But why were brooches with foreign associations chosen? Although these objects were brought from Britain for functional or sentimental reasons, they could have been passed on and used by other members of the community, who might have enjoyed a certain cachet deriving from their limited availability. Yet, instead they were buried to protect the deceased’s remains. Could it be that their particular associations with the deceased were valued, solidifying associations with the (dead) owner’s experience in Britain?

Another story emerges from the brooches located at sites associated with religious activity. These sites are also confined to areas where epigraphy attests that veterans settled after returning from Britain. The inclusion of objects of personal adornment in votive deposits suggests that people offered them for personal reasons. Indeed, selecting British-made brooches for the gift to the divinity indicates their totemic value. By depositing such an artefact in a ceremonial pit on a sacred site, veterans or their family-members may have sought to fulfil a vow or thank the gods for their protection in Britain, or perhaps symbolically bid good riddance to what had probably been an unpleasant military service. As such, the objects were elevated to a role in spiritual rather than daily life, probably because of their associations with military service in Roman Britain.

Seen this way, small, portable, personal finds give us real, physical evidence of human mobility between Roman Britain and the Continent, and augment the epigraphic evidence. Of course, not every find of a British brooch on the Continent can be explained by migration. At times, these objects did indeed arrive via trade networks, reaching areas where Britons presumably never imagined being, such as present-day Anapa in southern Russia (see CA 222). Contextual variation in the distribution and deposition of the brooches also indicates that these adornments could be imbued with many meanings, which were often dependent on the social group using them. Interestingly enough, in the frontier zones of the Roman Empire, these artefacts tend to be found in military ditches and rubbish pits. It seems that these troops, most of whom were British-born, regarded brooches as ordinary, unexotic, and valuable only for their original purpose of fastening clothes.

British travellers in a Roman world

In recent decades, interest in immigrants to Roman Britain has grown considerably (see CA 266). Yet all too often emigrant Britons are forgotten, as if the island only attracted people, and did not export them. While some ideas presented in this article must be deemed speculative, we need to find ways to flesh out the meagre epigraphic evidence. For now, it seems clear that British-born people travelled throughout the Roman Empire, taking British-made objects with them. Such evidence challenges the long-held preconceptions that Britons showed little interest in travelling to and around the Continent. Overcoming such received wisdom opens up a wealth of new possibilities to test, and affords an altogether more nuanced understanding of the role of Britain, its people, and their objects in the Roman world.

This article appears in CA 311. Click here to subscribe!

Images: Colchester Museum/Portable Antiquities Scheme ESS-142D56; Musée Gallo-Romain de Fourvière; Het Valkhofmuseum, Nijmegen, the Netherlands